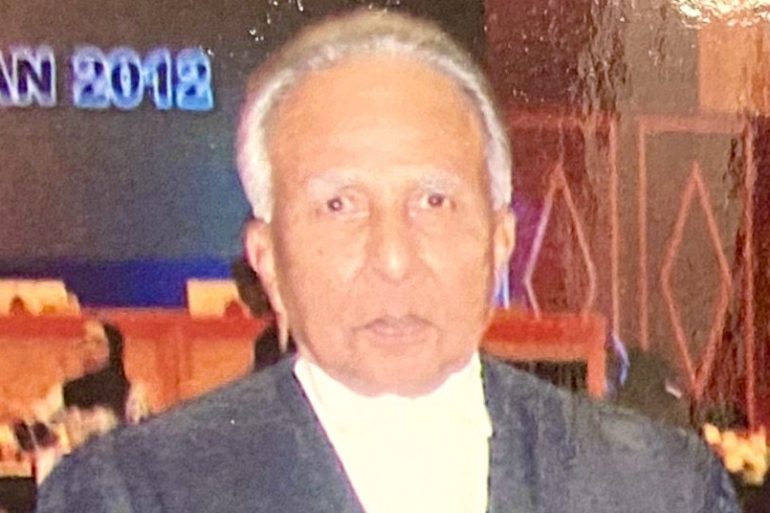

Aaron Abraham, the Law Lecturer, and a difficult question

Mr Abraham was something of a mystery. Taciturn and inscrutable, he showed a combination of humility, compassion, industry and stamina that few of us can dream of.

Aaron Abraham was 59 when we met. We read for the Bar Exams.

Taciturn to a fault, he sat right at the back and took notes quietly.

Aaron was a retired senior police officer

He had spent decades prosecuting criminals and had mastered the Law of Evidence and Criminal Procedure.

That he had to sit for the Malaysian Bar exams was, to him, a mere formality, and so he bore with it.

We sometimes had to deal with lecturers who had had little legal experience to speak of.

They would have completed their basic degree, gone through the Bar exams, could have had a fleeting career; and would have come into university to teach those who would eventually end up in practice.

It was not an ideal situation: but we had to deal with it.

It was worse for those of us who had come from British universities.

There, thinking was a necessity, not an occasional privilege handed out by a lecturer.

In Malaysia, during our time, thinking meant you had to put out in exams, exactly what the lecturers taught you. Intellectual indigestion was in, thinking was out.

If you indulged in legal creativity, where you would be singled out for praise and high marks in a Western university, you became the object of ridicule and failure in a Malaysian one.

The Bar exams are practical courses

Students often asked awkward questions. A lecturer’s answers often laid bare his or her inexperience. This lack of experience often manifested in the lecture hall.

Aaron and I went through this terrible ordeal. He did it quietly.

Which brings us to this particular lecturer …

She was full of herself. She had had not been in legal practice at all, and it always and always showed.

And she was resentful of English graduates. She did nothing to hide her scorn.

She boasted during lectures that ‘many’ legal practitioners constantly sought her out for her for her ‘opinions’.

The message was, ‘I am good, and you have better acknowledge it’.

Aaron would not bat an eyelid when he attended her lectures.

There was a reason for his silence

If you knew him, there was a reason for his silence: he was busy thinking.

He was constantly turning legal concepts over in his mind. And it was always about the law.

‘Can this be legally done?’

‘If the facts were slightly different, would the judges have reached a different conclusion?’

‘If so would it have changed the legal landscape?’

‘Suppose we applied this hypothetical principle to a recent case where a man was seated to death. Would he have escaped the gallows?’

That was Aaron for you.

And he was so busy with thinking he had no time to criticise anyone, least of all his lecturers.

Sometimes, just sometimes, I could discern a change

One day, this lady lecturer was in full flight, in answering a question: how do you justify having exceptions to the Hearsay Rule?

The court would never accept the evidence of Witness A if A said in court that the accused was guilty of an offence because her friend B had said so.

The court would not normally believe what A said: unless B was brought into court and cross-examined by the Defence team.

If not, any accused would be convicted purely on the say so of someone who came to court and said, ‘I say D is guilty because my friend B, who is not here by the way, said so’.

That the court would not allow. To convict someone on this sort of evidence would set a dangerous precedent: and this was a well-entrenched principle.

The lawyers called it ‘the Rule against Hearsay’.

Are there exceptions to the Hearsay rule?

But the court would accept the evidence of a witness who would repeat in court the whisper of a dying victim, who had said to the policemen, ‘D was the one who shot me’.

So the question was, why should this be allowed?

Well, there were several explanations and one stood out in particular: over hundreds of years judges had classified it as a ‘Dying Declaration’.

When a victim has accepted she is about to die and was ready to meet her Maker, anything she said to a third party made it acceptable in court – even if it was someone else – a police officer, or her mother, or a friend, or even a complete stranger.

All that the hearer had to do was to turn up in court to repeat what the victim had said before her death.

That was the explanation.

It was not a perfect explanation, nor a safe one, but there it was.

What if the witness had a bad motive?

One of the students asked:

‘What if the police officer was lying?’

What if the witness in court hated the accused and was bent on sending him to the gallows by a fabricated ‘dying declaration’?

The lecturer’s answer to the question

This lady lecturer gave an unbelievably boring, circuitous and ridiculous explanation.

Listening to this drivel, I turned to Aaron, expecting to see his usual stoic, resigned expression.

I heard a snort.

Aaron’s eyes seem to say, ‘That is not quite right, is it?’

I sought him our after lectures and asked what he thought of what she had said.

He smiled indulgently and stared into his cup of coffee for some minutes.

I pushed him.

He eventually recited a series of cases, the questions they had posed, and the decision in each case.

His legal trip into time began with an English case, an Indian appeal to the Privy Council, a series of decisions made by the Indian Supreme Court, and then on to an old Malaysian Federal Court case.

I will not bore you with the details, except to say that he traversed the legal architecture of five decades, a trip into the minds of the judges of the Privy Council, the Indian Supreme Court, the authors Cross, Woodroffe, and Sarkar – and after ten minutes of this Time Tunnel Trip he asked,

‘So, do you think she was right?’

We became close friends. He was the teacher; and I, an acolyte awaiting his wisdom.

The rest of the story is in this video, but…

Neither this story nor the story in the accompanying video does him any justice to the man he was, or to the lawyer he became or to the honour and integrity he displayed in his personal and professional life.

He is a living legend: one of the most loved doyens of the Malaysian legal profession.

I am proud to be one of his friends.

This is but one story of him.