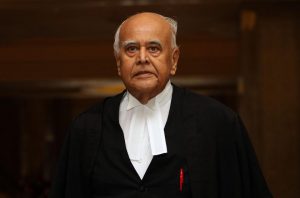

The Gopal Sri Ram I knew

He brought a level of legitimacy and credence to an institution that had been staggering under the weight of the 1988 judicial crisis.

[1] The Gopal Sri Ram that I knew

Your excellencies and colleagues of the Bar.

We are here to remember Datuk Seri Gopal Seri Ram: the man, the lawyer, the judge. What better way is there than to recite a prayer for the ascension of and assistance to his soul?

Could I with your permission, recite a brief prayer of Abdul Baha from Baha’i Scriptures?

[2] Prayer

O my God! O Thou forgiver of sins, bestower of gifts, dispeller of afflictions!

Verily, I beseech thee to forgive the sins of such as have abandoned the physical garment and have ascended to the spiritual world.

O my Lord! Purify them from trespasses, dispel their sorrows, and change their darkness into light. Cause them to enter the garden of happiness, cleanse them with the most pure water, and grant them to behold Thy splendours on the loftiest mount.

[3]. How he lived and loved the law

Datuk Seri Ram was my pupil master and my employer.

[4] Character

The character of Sri Ram requires no great explanation: he was focused and to a fault, industrious. He came to work at 6.00 a.m. He spared no expense over research materials. He conducted his own research – and remembered them all.

[5] At the Bar

In 1994, he ascended directly to the Court of Appeal, equalling a precedent Lord Goff had set. He graced the Court of Appeal bench for a good 15 years. There is a reason for that, as we shall see later.

In 2010, he retired from the judiciary; and the next day, he appeared at 6.00 a.m. before the Chambers of Messrs Soo Thien Ming where he was invited as partner; and demanded to know why the office was closed.

Other than the law, he had no other love. His work was his Life.

[6] Ram’s arrival as counsel at the Federal Court

In one early example in 1976, which made his career, concerned a Dr Dutt, a radiologist at the Assunta Hospital.[1]

Dutt was an expatriate. His employers fired him. The Minister of Labour referred the dispute to the Industrial Court. Sri Ram took up the case. At the High Court, Ram was led by a man he revered: RR Chelliah.

The hospital argued that the Industrial Court had no jurisdiction to hear the dispute. The Industrial Court ruled in Dr Dutt’s favour.

When the matter ended up before the Federal Court in 1981, a young Sri Ram took on his opponents – all alone.

The question there was whether the court’s award of compensation – instead of reinstatement – had been made without jurisdiction. The High Court thought so: it quashed the Industrial Court award.

Ram argued even if an award of compensation contained errors upon its face, those errors did not give the High Court jurisdiction to quash the Industrial Court’s decision. Ram would argue exactly the opposite 30 years later. We shall come to that shortly.

The next question was whether, Dr Dutt, a radiologist, was a ‘workman’ under the Industrial Relations Act 1967. Section 2 of the Act gave Ram serious problems. If it was literally interpreted, Dr Dutt would be in trouble. The decision in his favour could be successfully attacked.

To get around sec.2 of the Act, Sri Ram argued that the word ‘and’ in sec.2 of the Act, should be read as if it was ‘or’.

The Federal Court agreed with him.

The word ‘and’ combines two concepts. It is therefore a conjunctive.

The word ‘or’ divides two concepts, and was therefore a ‘disjunctive’.

So, Ram changed a conjunctive into a disjunctive.

[7] Ram as counsel in court

When he was in court, Ram was at his best. As opposed to his natural disposition, he was courteous.

He would get straight to the point.

He was devastating in reply. When an opponent was adventurous, and made strong points against him, he would immediately send his junior sprinting down to the court library to procure several cases. In reply, he would then recite them with destructive effect.

When he sat on the Bench, he disapproved counsel concluding arguments with the words: “I therefore humbly submit…”. He often reminded lawyers not to be ‘humble’.

“We have a job to do. We do that with confidence, and courtesy. We are never humble”.

[8] Harnessing a legal point

Ram never made notes. He spoke completely from his mind. He could describe his case, its factual matrix, the issue in dispute, the questions of law, the weaknesses in his opponents casehow the court should decide the case – all in 5 minutes. This is the greatest quality of a world-class counsel: and Nani Pakhivalla was its greatest exponent. Ram would use Palkhivalla’s technique again and again.

Always a bit of a showman, he loved to exhibit his knowledge of the law.

Despite this vanity, (which Palkhivalla never allowed to cloud his mind), Ram’s knowledge was real and deep.

[9] How Ram announced his arrival at the Judiciary

The opening knell that Ram had arrived, as counsel, was in the Dr Dutt case.

That Sri Ram was a force to be reckoned with was the came in a case called Syarikat Kenderaan Bas Melayu Kelantan v Transport Workers Union.

This was in a 1995 case. Ram was confronted with section 33B (1) of the Industrial Relations Act. Any decision of the Industrial Court was final and conclusive.

To avoid sec 33B, Sri, Ram argued that the Industrial Court, being an inferior tribunal, had no jurisdiction to commit an ‘error of law’. Such an error could not be, in his resounding words, ‘immunised from judicial review by an ouster clause, however widely stated.’

In that case, he declared the House of Lords case of South East Asia Firebricks, especially the speech of Lord Diplock, in it to be wrong. Who would dare do that?

[10] Which now brings us to the question of his influence on the law.

For the first 15 years of his career as a judge, he developed commercial law, contract, and the law of estoppel.

He began developing constitutional law in the last few years of his time on the Bench – which is pity.

[11] The 2009 case of Lee Kwan Woh v. PP was an early exception

In Lee Kwan Woh v. PP, he postulated the ‘prismatic’ method of interpretation. His words have now passed into legend:

“When light passes through a prism, it reveals its constituent colours. In the same way, the prismatic interpretive approach will reveal to the court the rights submerged, and the concepts employed by the several provisions under Part II [of the Federal Constitution]. Indeed, the prismatic interpretation of the Constitution gives life to abstract concepts such as ‘life’ and ‘personal liberty’ in Article 5(1).”

That the Constitution was a living piece of legislation was a point he constantly brought home.[2]

Inspired by Lord Wilberforce’s speech in the Privy Council case of Minister of Home affairs v. Fisher, Ram argued that the provisions in a constitutional document were ‘sui generis’ – meaning that they constituted a class alone, and were unique. Thus, a constitutional instrument was not to be interpreted by slavish adherence to established precedents of statutory construction.

A keen observer of English law, Ram would seize upon Fisher 30 years later in Lee Kwon Woh, to bring it home.

So, he enhanced the old – but forgotten – principle that Constitutional rights had to be interpreted liberally. Any Parliamentary restriction of those rights had to be construed strictly, even narrowly.

[12] Some notable cases

How could we forget how Ram converted the fundamental concept of ‘right to life’ as being as ‘right to livelihood’ in Tan Tek Seng; or his recognition of indigenous people’s usufructuary rights [meaning, rights over land] in Sagong Tasi?

Too many are cases illuminating the greatness of his defence of the Constitution.

In this way, Sri Ram single-handedly developed the law of the Constitution. Importantly, he liberated it from the clutches of pro-establishment judges of the 1960s and 70s.

Eight hundred of his judgments, like beacons, light the way of the Malaysian judiciary and the Bar alike. He protected the weak against the strong. He fought injustice. Sometimes he succeeded. Sometimes he failed. But it never stopped him from appearing in court, even after his retirement, to challenge oppressors.

[13] Ram brought legitimacy to the Bench and the Bar

He brought a level of legitimacy and credence to an institution that had been staggering under the weight of the 1988 judicial crisis.

There was a time when Singapore judges would refuse to cite Malaysian cases. Ram broke that trend. Soon he was regularly quoted by the Singaporean judiciary.

As a judge, he took several judges under his wing. He taught them as much as he could. Many judges recall this with gratitude. They speak fondly of him.

[14] Controversial

He was perhaps one of the more controversial judges we have ever had.

There were several cases in which he plunged his feet into hot water.

In one Court of Appeal case, he attacked the patronage of two infamous politicians, for having influenced the successful procurement of a contract. That costs a great deal.

That was but one case: there were others. Similar controversies dogged his otherwise brilliant career: and they delayed his ascendancy to the apex court by at least a dozen years: one is reminded of Ram’s own ‘piscular’ maxim: even a fish would not get into trouble under certain circumstances.

Yet, shall we light a candle or curse the darkness?

[15] Life and Work

Sri Ram’s life and his work are reminiscent of Lord Atkin’s dissenting speech in Liversidge v. Anderson.[3] There Atkin stated, regarding a man arrested during the war, that ‘amid the clash of arms, the laws are not silent’.

Lord Atkin said,

“It has always been one of the pillars of freedom, … that the judges are no respecters of persons and stand between the subject and any attempted encroachments on his liberty by the executive, alert to see that any coercive action is justified in law. …

I protest, even if I do it alone, against a strained construction put on words with the effect of giving an uncontrolled power of imprisonment to the minister.”[4]

Ram spent his entire life doing exactly this.

[16] Courage

After his retirement, Ram took on powerful political individuals. You know he was involved in the prosecution of several high-level cases. That took courage. And Ram loved the publicity and the adulation it brought him: in this, his conduct is reminiscent of Denning’s ambitious nature, and how Denning had exploited the Profumo Inquiry to get ahead of his competition.

[17] Arjuna

I am sure you know of the Indian epic, Mahabaratha. Might I remind you of a philosopher’s analysis of why Lord Krishna guided Prince Arjuna during the Mahabharata War?

Arjuna was vain. He was replete with flaws. Yet he was an archer without peer. His arrows never missed their mark.

Yet, when the time came to lead the charge into battle at Krushetra, Lord Krishna, representing Godhead, chose Arjuna. Intriguingly, Krishna became his charioteer, guiding Arjuna – through his personal travails and doubts – to the final victory: and thereby hangs a tale.

It is a parable of life itself.

Ram never turned away those who who sought his help. That one character overrides every other flaw in his personality.

[18] Sacrifice

He came to court despite his many ailments. He once said, ‘Don’t talk to me about pain. I am in constant, excruciating pain. And yet, here I am.’ And this was before he was wheelchair-bound. And even then, he was present at court.

[19] Which position does Sri Ram occupy?

Does Ram occupy the same rank as Lord Atkin, Thomas Jefferson, ‘Homi’ Seervai, Nani Palkhivala, Chief Justice John Marshall, Chief Justice Dixon, Learned Hand, Lord Denning, or Lord Neuberger?

You decide.

Certainly, late Datuk Seri Gopal Sri Ram occupies a special place, for Kálá, the God of Time itself cannot dislodge him from that Roll of Honour.

Though his life is now extinguished, the light in his words, his example, his industry, his tenacity, his stamina, his crystalline arguments, his sudden turns of English – these live in our hearts.

Like Arjuna, Ram was brilliant, and suffered from many flaws.

But what a man has done by his deeds, speak louder than his words.

The cage is broken, but the bird of the soul is free.

I pray, like you, for the late Datuk Sri Gopal Sri Ram’s soul.

Footnotes

[1]. [1980] 1 MLJ 96]

[2]. His Majesty the late Lord President Raja Azlan Shah said, in the 1981 case of Dr Menteri Othman Baginda & another v. Dato Ombi Syed Alwi Syed Idrus.

Gratitude

I thank Miss Geetha Kesavan Nair and Prabkhirat Singh for helping with editing and publication.