Is the King’s power to grant a pardon, ‘personal’ and ‘absolute’?

Some say that the power of the King to grant a royal pardon is ‘absolute,’; that ‘no one can question it’. Is this correct?

Some say that the power of the King to grant a royal pardon is ‘absolute,’; that ‘no one can question it’.

[1]. Is this correct?

In my opinion, the answer is a ‘No’.

I will explain.

[2]. First, some fundamental principles of constitutional law

[2-1]: What is meant by the King’s ‘discretion’?

It means, that sometimes the Federal Constitution gives the King a greater freedom to decide certain issues.

Does such ‘greater’ discretion mean ‘absolute power’?

Thus, does the King have any ‘absolute’ power over pardons?

To understand how the Constitution deals with this concept, we need to recall some fundamental principles of Rule of Law, and Constitutional law.

[2-2]. First, as de Bracton established about 800 years ago, ‘No one is above the law, not even the King’.[1]

[2-3]. Second, as Constitutional Monarch, the King must act ‘… in accordance with Malaysia’s laws and Constitution’ … and uphold the rules of law and order in the Country.’[2]

[2-4] Third, the King cannot act on his own.

The King has several persons who advise him.

[3]. Is the King obliged to comply with their advice? Mostly, yes.

But in four situations, the King can act in his ‘own discretion’:-

‘The [King] may act in his discretion: –

(a) in the appointment of a prime minister;

(b) in refusing to dissolve of Parliament;[3]

(c) in requiring a meeting of the Conference of Rulers over the powers of the royal houses; and;

(d). ‘in any other case mentioned in [the] Constitution.’[4]

[4]. What does ‘any other case’ involve?

In short, those powers do not concern the powers of pardon.

I have cited these in the endnotes here.[5]

[5]. How and who appoints the Pardons Board?

The King appoints members of the Federal Territory Pardons Board.[6]

The respective State Rulers, or governors, appoint the Pardon Boards of their individual states.[7]

The King presides over the FT Pardons Board, which comprises five other persons: –

[a]. the Attorney General,

[b]. the Minister for Federal Territories and,

[c]. three other members appointed by the King.[8]

So, all in, six.

[6]. Where does the King’s power to pardon come from?

It is in Art. 42(1).[9]

[7]. How does the King exercise his powers when granting pardons?

The Constitution states, rather cryptically, that:-

‘The Pardons Board must meet ‘in the presence of the [King] and he shall preside over it’: [10]

Because [the King] ‘preside(s) over the Pardon Board’, does it mean the King has overriding powers over the Board?

No: in my view, Art. 42(8) and clause (9) set out a formula on how the Board must act.

[8]. Does the Board ‘advise’ the King?

Of course it does.

Article 42 clause 8 is an ‘Operational provision’. It states: ‘the Pardon’s Board must tender its advice’….

Before that, look at what Art. 42(9) says:-

‘Before tendering their advice on any matter, a Pardons Board shall consider any written opinion which the Attorney General may have delivered thereon.’

So no choice there. The Board must hear the AG out.

[9]. Thus, the ‘advice’ is a two-step process

First, the AG must render his ‘opinion’ to the Board.

After that, the Board takes its next step.

[10]. Art 42(9) states that the Board, ‘having considered the AG’s opinion’, needs to ‘tender their advice’.

‘Tender their advice’ to whom? Obviously, the King.

Can the King ignore such ‘advice’?

No. Why? Because of a constitutional amendment.

Before 1994, Malaysian courts had ruled that the King’s discretion on granting pardons was ‘absolute’.

[11]. That would change after the 1994 Constitutional Reform

Art 40(1) had, from the beginning, stipulated that the King must comply with the Cabinet’s advice.[11] If the Cabinet advised the King to decide in a certain way, the King had no choice. He had to comply.

This clause need not have been there at all. The ‘compliance principle’ has been well-accepted for almost 800 years all across common law jurisdictions.

The convention required the monarch’s compliance with those authorised to advise the monarch. But Malaysia put it in expressly, anyway: just to ensure no one forgot.

On 24.6.1994, a constitutional amendment diluted the King’s power. The amendment went even further.

The Parliament inserted an additional clause, ‘IA’, into Art. 40.[12]

Clause 1A has been sitting in the Constitution for 30 years.

It is the most crucial clause on the question of the King’s power over a petition for a pardon.

What does it say? It makes a sweeping statement.

Article 40, clause 1A stipulates that:

‘… [In] the exercise of his functions under this constitution …,

‘where [the King] is to act in accordance…

with advice, …

‘on advice, …

‘or after considering advice, …

‘[the King] shall accept …

‘and act in accordance with such advice.’

Crystal clear.

If the Pardons Board advises the King to treat a petition of mercy in a certain way, the King must comply with the advice of the Pardons Board.

His Majesty, with respect, has no choice.

[12]. So how did the Malaysian courts treat this amendment?

They skirted it. Post-1994 Malaysian cases persist in the old view: that the ‘King’s discretion is absolute’.[16]

In one 2020 High Court case, Justice Akhtar Tahir ruled that the King must accept and act on the advice of the Pardons Board.[13] His reasoning is consistent with Art. 40(1A).

Yet, on appeal, the Federal Court overturned Justice Akhtar’s ruling.[14] It ruled that the King’s exercise of the power of pardon is ‘absolute’, and ‘non-justiciable’: meaning, the courts cannot question it.

This is rather confusing. And at odds with other leading commonwealth cases, which suggest that this power is not ‘absolute’. [17]

[13]. There is a conflict between what the Constitution states and how our courts have ruled on that point.

In my view, when there is a conflict between what the courts say, and the express and unambiguous words of the Constitution, the Constitution prevails.

Article 4(1) of the Constitution states:

‘This Constitution is the supreme law of the Federation: and any law passed after Merdeka Day which is inconsistent with this Constitution shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void.

Art. 40(1A) of the Constitution clearly states that the King must ‘act in accordance with … advice, or after considering advice’.

With the greatest deference, in my opinion, the King does not have power to, or grant any pardon, on terms different from that advised by the Pardons Board. [15]

[14]. There is now a question that bothers a great many people in Malaysia.

It is this: ‘What did the Pardons Board advise the King?’

Is the proceedings of the Pardons Board a secret?

@Copyright reserved.

All content on this site, including are the intellectual property of GK Ganesan Kasinathan and are protected by local and international copyright laws. Any use shall be invalid unless written permission is obtained by writing to gk@gkganesan.com

Endnotes

[1]. The medieval jurist Henry de Bracton observed in his treatise,’On the Laws and Customs of England’, that ‘The law makes the king and, therefore, the king must be subject to the law.’ This was written between 1220 and 1260 during the reign of Henry III London: Richard Tottel, 1569. Law Library, Library of Congress

[2] . ‘Art. 37. (1) The Yang di-Pertuan Agong shall before exercising his functions take and subscribe before the Conference of Rulers and in the presence of the Chief Justice of the Federal Court (or in his absence the next senior judge of the Federal Court available) the oath of office set out in Part I of the Fourth Schedule’.

[3]. Read Art. 40(2) with Art. 55

[4]. Art. 40(2)

[5]. The ‘any other case’ in two places in the Constitution refer to Article 55 and several governmental appointments. Art. 55 speaks of the King’s discretionary power to summon, prorogue (or postpone) or dissolve Parliament. The second set of provisions relates to the King’s right to appoint (and remove) members of Commissions. In all these cases, the King must act in accordance with the Cabinet advice.

[6]. Article 42

[7] Art. 42(5)

[8]. See Art 42(11), which modifies Art 42(5) and (6).

[9]. It reads, ‘[The King] has power to grant pardons, reprieves and respites in respect of … all offences committed in the Federal Territories…;’.

[10] See article 42(8), and (11). The King’s power to grant a royal pardon is housed in Article 42 (especially, clauses 1, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 11).

[11]. Art 40(1): ‘In the exercise of his functions under this Constitution or federal law the Yang di-Pertuan Agong shall act in accordance with the advice of the Cabinet or of a Minister acting under the general authority of the Cabinet, except as otherwise provided by this Constitution; but shall be entitled, at his request, to any information concerning the government of the Federation which is available to the Cabinet.’

[12] Constitution Amendment Act 1995

[13] Mohd Khairul Azam bin Abdul Aziz v Lembaga Pengampunan Wilayah Persekutuan [2020] MLJU 1691. See para [36].

[14] Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim v. Mohd Khairul Azam Abdul Aziz & Anor appeal [2023] 2 CLJ 236.

[15] See Article 40 (1A)

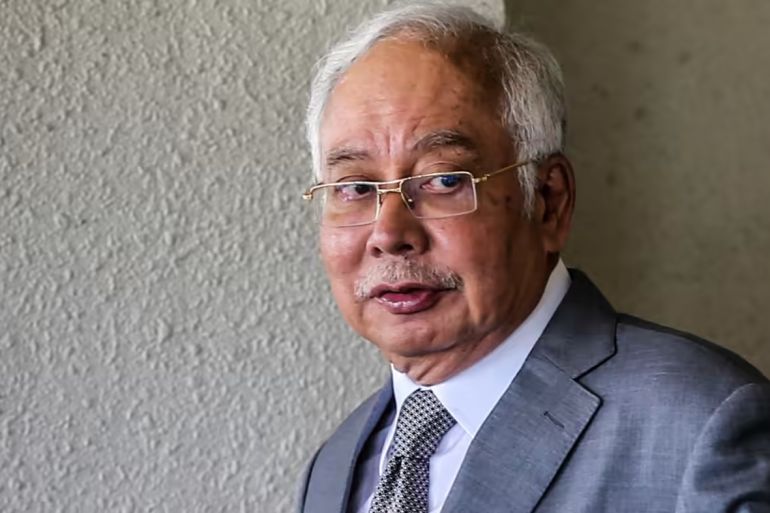

[16] For Pre-1994 cases, see Council of Civil Service Union v. Minister for the Civil Service [1984] 3 All ER 935; e.g. PP v. Soon Seng Sia Heng & Other cases [1979] 2 MLJ 170; Chiow Thiam Guan & Ors v Superintendant of Pudu Prisons & Anor [1983] 2 MLJ 116; Sim Kie Chon v. Superintendant of Pudu Prison [1985] 2 MLJ 385; Karpal Singh v Sultan of Selangor [1988] 1 MLJ 64. For post-1994 cases, see YAM Raja Dato Seri Hj Izzuddin Iskandah Shah ibni Almarhum Sultan Idris A’fifullah Shah v. Dewan Negara Perak Negeri Perak, & Anor [2010] 2 CLJ 767; Juraimi Hussein v Pardons Board of State of Pahang & Anor [2002] 4 CLJ 529.See also Tun Dr Mahathir bin Mohamad v. Dato Seri Mohd Najib bin Tun Hj Abdul Razal & Ors [2018] 8 MLJ 297, at p. 298.

[17]. See Mc Geough v Secretary of State for Northern Ireland [2012] NICA 28, R (in the application of Shields) v. Secretary for Justice [2008] ALL E R (D) 182 (Dec); R v Foster; the Indian Supreme Court in Kehar Singh and Anor v. Union of India and Anor [1989] AIR 653

[The author expresses his gratitude to Ms KN Geetha, Mr. Thinagaran Batumalai, Ms Shalini Ragunath, Ms Pavaani, Ms Lheela, and En. Abd Basiir Kohar for their assistance in researching this article].